Origins of Alpha: Why Does Alpha Exist? How Can One Capture It?

An exploration of my views on harvesting excess returns in public markets.

Welcome back, everyone! I spent the last ~4 months working and learned a lot from my experiences. I’m excited to restart this Substack. The goal is for ~1 Substack/week and for them to be more concise (after this week!). I would love any feedback on my writing or thought processes. (ejn2@williams.edu)

Introduction

I’ve previously written about where alpha is generated and posited there are two main sources of alpha: 1) Understanding fundamental relationships better than other players and 2) Modeling fundamental relationships better than other players. I’ve since expanded my view on alpha and in this piece, I document and quantify these new views. My position can be summarized as follows:

Alpha is very difficult to find and simply knowing where to look for it can provide a serious edge to market players.

Alpha can be captured by trading against less-informed players. (Informational Alpha).

Alpha can be harvested by trading against non-economic players (defined later) (Utility Arbitrage Alpha).

Generally, the Informational Alpha is probably easier to find in more illiquid, smaller markets than in liquid, large markets.

Utility Arbitrage Alpha can occur in all markets, but in practice is probably more common in large, liquid markets.

It’s important to always understand which alpha you are trying to capture. If you don’t know where your differentiation is, you’re likely to be handing alpha to your counterparty!

Roadmap

Defining Alpha and Market Inefficiency

Informational Alpha

Theory

Practice

Future

Utility Arbitrage Alpha

Theory

Practice

Future

Conclusion

Appendix

Defining Alpha

If Markets are Efficient, There is No Alpha

Let us first define “alpha.” Definitions of the word can vary, but I define alpha as excess risk-adjusted return. Very simply, I think we can define risk as variance because variance1: 1) is correlated with risks investors care about (drawdowns, defaults, risk of permanent loss) and 2) It is rather easy to measure. Thus, an “alpha trade” can be defined as a trade with a higher expected return for a given volatility level than a corresponding index.

In efficient markets, all securities fully reflect all available information and thus no security is relatively undervalued or overvalued. This implies that there are no “alpha trades.” If Security A has an expected return of 8% with a variance of 6% and Security B has an expected return of 10% with a variance of 6%, investors would buy Security B while shorting Security A until their expected returns converged. In an efficient market, available information would allow all investors to properly assess the expected return of each security, and the arbitrage opportunity would never even exist!

I take this statement one step further—alpha is the byproduct of an inefficient market. Alpha trades are simply trades that capitalize on the inefficiencies of the market (and these inefficiencies do exist!). Deep fundamental research can expose inefficiencies due to others misunderstanding key points about the market, enabling funds to snap up securities trading cheaply. Quantitative analysis can capitalize on inefficiencies that are perhaps harder to see—finding signals that are hidden, but nonetheless real. Thus, if alpha exists, markets must be inefficient and all alpha is a byproduct of market inefficiencies.

Informational Alpha

Informational Alpha — Theory

The first type of alpha is probably the one that most people are more familiar with. This alpha arises because the shrewd investor understands certain aspects of markets better than other market players. I call this “Informational Alpha.”

As I’ve previously touched on, I believe Informational Alpha comes from two main, similar sources:

Understanding Fundamental Market Relationships Better Than Others.

Measuring Fundamental Market Relationships Better Than Others.

I’ll elaborate on both of these, but I think they are mostly the same. Both sources of Informational Alpha necessitate the trader to claim they are smarter than the market in some clear way. Perhaps this is true—and I tend to believe this statement has been true for certain players historically—but it is nevertheless a rather bold statement to claim. I find some difficulty in arguing that true, sustainable edge could be derived from this type of alpha as it requires continuously having a nuanced, better understanding of market forces than other players. As soon as others find out how you 1) understand fundamental relationships or 2) measure relationships, the alpha disappears and you have to start from Square 1. I do believe IA exists, but I think there is less IA than most commonly think.

Informational Alpha — In Practice

This is all rather abstract, so let’s look into two examples. First, let’s focus on Informational Alpha in Large Liquid Markets (LLM). Historically, having informational alpha in LLM has been a particularly profitable endeavor. John Paulson’s “Greatest Trade Ever,” is a good example of Informational Alpha in a LLM. John Paulson had a deep understanding of the subprime mortgage market along with structuring trades that enabled him to make a killing in a large market.

Leading up to 2008, the U.S. housing market had experienced a significant boom, driven by easy credit, low interest rates, and lax lending standards. This boom was particularly pronounced in the subprime mortgage market, where loans were extended to borrowers with poor credit histories. Many of these loans were packaged into mortgage-backed securities (MBS).

By 2006, John Paulson and Paulson & Co. identified several key vulnerabilities in the housing market and the financial products tied to it:

Bullish Housing Price Assumptions→They recognized real estate was frothy and that homeowners had taken on mortgages they couldn’t afford if home prices stopped rising.

Risky Loan Structures→The subprime mortgages were often structured with teaser rates that made them susceptible to default.

Flawed Assumptions in Other Investors' MBS Models→Many traders used pricing models that assumed housing price appreciation and low default rates.

Very clearly, Paulson had a superior understanding of the mortgage market than others and he profited handsomely when his thesis played out. As home values began to fall in 2008, defaults rose and the value of many MBS collapsed. Paulson & Co made $15billion for investors on these trades. Paulson’s Informational Alpha in a Large Liquid Market is owed to his deep understanding of the structure and risks associated with subprime mortgages along with an appreciation for security selection.

Now, let’s look at Informational Alpha in a Small, Illiquid Market (SIM). Whereas I think macro assets are a good example of a LLM, I think distressed credit is a good example of a SIM. It helps that I now have some distressed experience after the summer, but I’m obviously not allowed to write much about that in any real detail. Informational advantages here are less publicized and just for fun, I’ll make up a hypothetical example of an informational advantage in one of these markets.

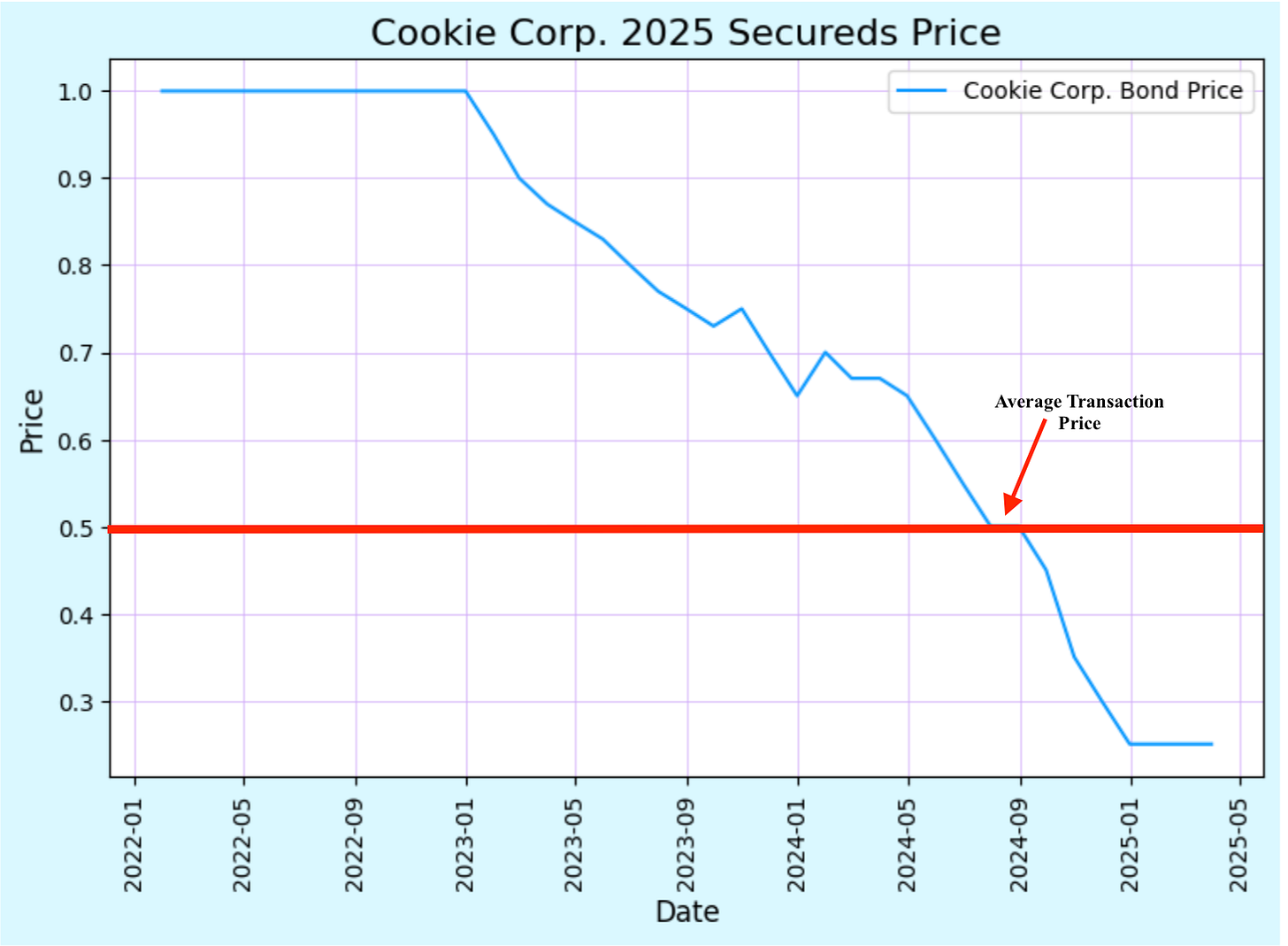

In distressed world, there are often only a few players looking at any particular name. For simplicity, let’s say there are two firms (Firm Apple and Firm Banana) looking at the debt of the Cookie Corporation—a baking company2. Cookie Corporation has fallen on extremely hard times after the price of cocoa skyrocketed earlier this year (Figure 1). Unlike their competitors, Cookie Corp didn’t hedge their commodity exposure.

Figure 1: Global Cocoa Prices

With higher input costs, Cookie Corp originally tried to raise prices significantly, but they experienced weakening demand and falling market share. With a high debt burden and soaring interest costs, Cookie Corp looked headed for a restructuring. Assume Cookie Corp only has one tranche of debt and it matures on January 1, 2025 (‘25 Secureds) (Figure 2). It currently trades at $.55.

Figure 2: Cookie Corp Simplified Cap Structure

Firm Apple has owned Cookie Corp debt for over a year and has followed the company closely. They think there are likely two main outcomes for Cookie Corp (all outcomes, probabilities, and valuations shown below) (Figure 3):

Cookie Corp declares bankruptcy, the equity is wiped out, and the lenders take control of the company.

Cookie Corp experiences a recovery in demand and narrowly avoids bankruptcy. The debt is paid off at par.

Figure 3: Firm Apple Valuation Scenario Analysis of Cookie Corp Debt

Thus, Firm Apple values the debt as worth $.63.3 The debt is currently trading at $.55, so they’d be happy to buy slightly more at these levels.

Firm Banana has noticed that Cookie Corps competitor Crum Conquerors is likely increasing the supply of their signature chocolate chip cookie, increasing competitive pressures on Cookie Corp. Firm Banana has used satellite imagery to determine factory workers are working later and Crum Conqueror factories are producing more cookies than usual. They determine that the probability Cookie Corp enters bankruptcy is higher than Firm Apple thinks and that the valuations in each scenario are lower due to the higher competition (Figure 4).

Figure 4: Firm Banana Valuation Scenario Analysis of Cookie Corp Debt

Firm Banana thinks Cookie Corp’s debt is worth only $.24 and starts to short the debt4 which is currently trading at $.55. Firm Apple is the natural buyer here, but because Banana is more motivated (and initiated the trade), let’s say they exchanged $5million of bonds at an average price of $.50.

Now, Crumb Conqueror increases supply over the next six months, Cookie Corp is pushed into bankruptcy, the debt is converted to equity, and the equity trades at the debt equivalent of $.25. Firm Banana made significant profits on their trade (100% in half a year), while Firm Apple got severely hurt (Figure 5).5

Figure 5: Hypothetical Price Chart of Cookie Corps 2025 Secured Bonds

It’s quite clear that Firm Banana’s alpha was due to an Informational Advantage. They understood the competitive dynamics better than Firm Alpha and profited handsomely.

Informational Alpha — Future

In my view, an Informational Advantage in a SIM is relatively easier to find than in a LLM due to SIMs having significantly less competition. In the example above, in a larger market, more firms would have been more involved and likely would have spotted the increase in competitiveness quicker, preventing prices from becoming so inefficient.

However, there is a counterargument. Perhaps in larger markets, it takes more (quantity of capital) informed players to push markets to efficiency. If there are enough noise traders in a market, perhaps there can also be many shrewd investors that can trade against them. Think of NVDA. NVDA’s average daily volume is 340million shares, or $44billion. It takes A LOT6 of capital to move NVDA up or down.

However, to believe the view that larger markets have more opportunities for Informational Alpha, one must have extremely high conviction in the stupidity of the average market participant. Information in these names is extremely easy to come by and there are many eyeballs on every specific detail. If someone does find a “smoking gun”, it’s likely others also have. Importantly, it’s likely someone will publicize this and all participants will quickly be informed.

This takes us a level deeper. Perhaps, one could argue, informational advantage is easier to find in SIM, but there are enough stupid players in LLM that each market has equivalent difficulty in finding alpha. Well, I argue that Informational Advantage leakage is likely much higher in LLM, making IA alpha more difficult in LLM.

I define IA leakage as an informational advantage that one firm finds that is then “leaked” to the outside world. For example, in the case of Cookie Corp, IA leakage would be if somehow, someone from Firm Banana “leaked” the increasing competitive threat of Crumb Conqueror to Firm Apple. Immediately after this information leaked to Firm Apple, they would refuse to buy Cookie Corps bonds at anything above $.30, and the bonds would likely immediately trade down.

In SIM, by definition, very few people likely have Informational Advantage. Thus, there is a smaller likelihood this information is leaked. However, in LLM, many more traders may have IA. Moreover, there is a Game Theory component to IA in LLM. If we go with our premise that there are relatively more “dumber” investors in LLM, and it takes a lot of capital to move these securities, then investors who have informational advantages are likely to do the following:

Size Their Positions Fully in Accordance with their Informational Advantage

Make huge noise about this information and make sure “Dumber, Less-Informed” Investors Become Aware of This Information.

Sell Out of Their Trades When Prices Adjust to “Fair-Value”

Thus, IA in LLM is likely to be fleeting. As soon as one player finds such an advantage (and they fully size their positions), their incentive is to immediately alert all investors to this inefficiency, leading to the IA disappearing.7

Utility Arbitrage Alpha

Utility Arbitrage Alpha — Theory

Utility Arbitrage Alpha (UAA) is my name for a relatively broad set of circumstances. I define UAA as alpha one can harvest either by having different utility functions than their counterparties (perhaps you and your counterparty have different risk tolerances), different constraints (perhaps their risk manager stops them out if a position loses 3%+), or different objectives (central banks prioritizing policy over profit). In all these cases, you are, in effect, providing a service to “non-economy players” (NEPs). Some may also view this as harvesting risk premia, although I think this is a source of alpha.8

Now, just because there is a natural seller on the other side of the trade doesn’t make this an easy trade! First, NEPs are not necessarily suckers. They still want to get the best possible price for their trade. An airline hedging its fuel exposure may be “non-economic” in that they are buying aircraft fuel futures to hedge business risk, not because they have some view on fuel prices. But, they still would obviously rather get a better price than a worse price. Moreover, while the trades may be relatively uncompetitive on the counterparty side (non-economic players are willing to trade at worse than fair-value prices), many players are trying to capture the alpha from these flows. Thus, the trades can be very competitive from the demand side.

There is also an additional nuance that I may explore further in a different paper. Because investors are happy to trade against NEPs, certain economic players may try to disguise themselves as NEPs to get better prices. Thus, if you want to do UAA, you have to be very certain that your counterparty truly does have a different utility function from you—and they aren’t just pretending to!

Utility Arbitrage Alpha — Practice

Let’s first focus on Utility Arbitrage Alpha in a Large Liquid Market. The bread and butter of UAA in LLM are trading against large flows. Large flows from non-economic players have the potential to greatly dislocate markets. Let’s use the example of a large Canadian conglomerate with significant European operations that must hedge out its Euro exposure.

Perhaps every month, this company sells EURCAD in accordance with their profitability in Europe. For simplicity, let’s assume they repatriate all profits back to Canada at the end of every month. If they make €2 billion, they’ll sell 2bil of EURCAD on the last day of every month. There are two important things to note about this:

These flows are likely to move EURCAD away from “equilibrium.”

These flows are predictable but require some fundamental business understanding of the Canadian conglomerate.

Warren Buffett once said, “In the short run, the market is a voting machine, but in the long run, it’s a weighing machine.” I have a corollary to this: “In the short run, security prices are determined by flows, in the long run, they are determined by fundamentals.”

The extension of this logic, of course, is that by trading against flows, one can capture temporary dislocations and harvest alpha. After all, alpha is simply compensation for trading against market inefficiencies. If flows bump markets out of equilibrium, trading against flows captures the inefficiency. So, very simply let’s analyze this situation further.

The large Canadian conglomerate (LCC), has a utility function that is extremely averse to holding Euros. They like to do business in Europe but don’t want any Euro exposure. Perhaps their domestic investors don’t want FX risk or perhaps they have a real need to fund spending and growth opportunities in Canada and are using their European profits to expand their Canadian operations. Either way, they are actively trading in the FX market without having an informed view of the fundamentals of EURCAD.

The hypothetical hedge fund (HHF), has a utility function that solely prioritizes risk-adjusted returns. When LCC goes and tries to maximize their utility function (which has a positive parameter for selling EUR), the HHF can trade against them and maximize their profitability by buying EUR. LCC may bump EURCAD out of its fair value for a bit, but HHF will buy back EURCAD, trying to push it back to equilibrium (and collecting some alpha in the process).

The relationship between the Canadian Conglomerate and the Hedge Fund is rather symbiotic, allowing both parties to profit from the trade (the LCC profits in utility space while the HHF profits in profit space!). Moreover, perhaps HHF has an FX strategy that is able to understand where all these potential flows are coming from and can understand when markets are moving because of fundamental reasons or because of flows. If markets dislocate because of flows, HHF trades against the flow. If they determine markets have moved without any significant non-economic flows, they assume the fundamentals have changed.9

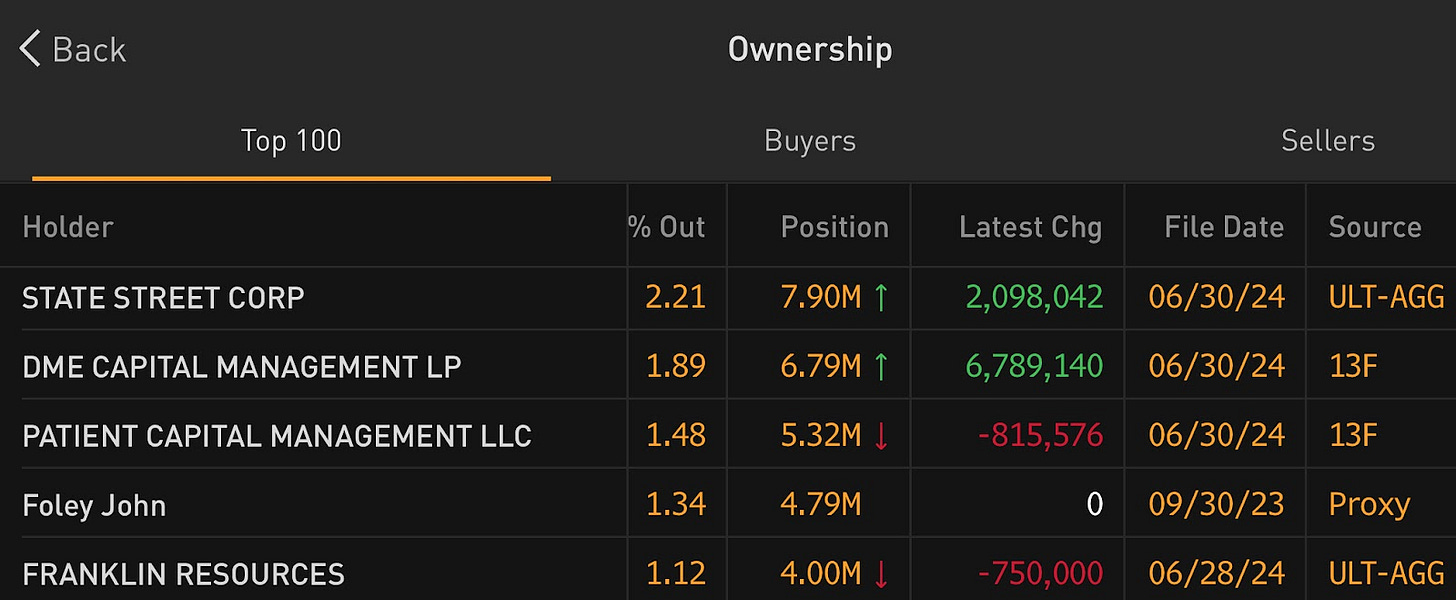

Now, let’s look at UAA in a relatively more illiquid market. John Foley is in the news, so let’s look at Peloton as an example. Peloton is currently trading at $4.84 and for simplicity’s sake, let’s assume this is the fair value of the equity right now. Foley currently owns 4.8 million shares, or ~$23million (Figure 6). Peloton is not illiquid, but it also isn’t very liquid as it trades $50mil per day. This example can be generalized further to more illiquid markets easily.

Figure 6: Condensed Ownership of Peloton Stock

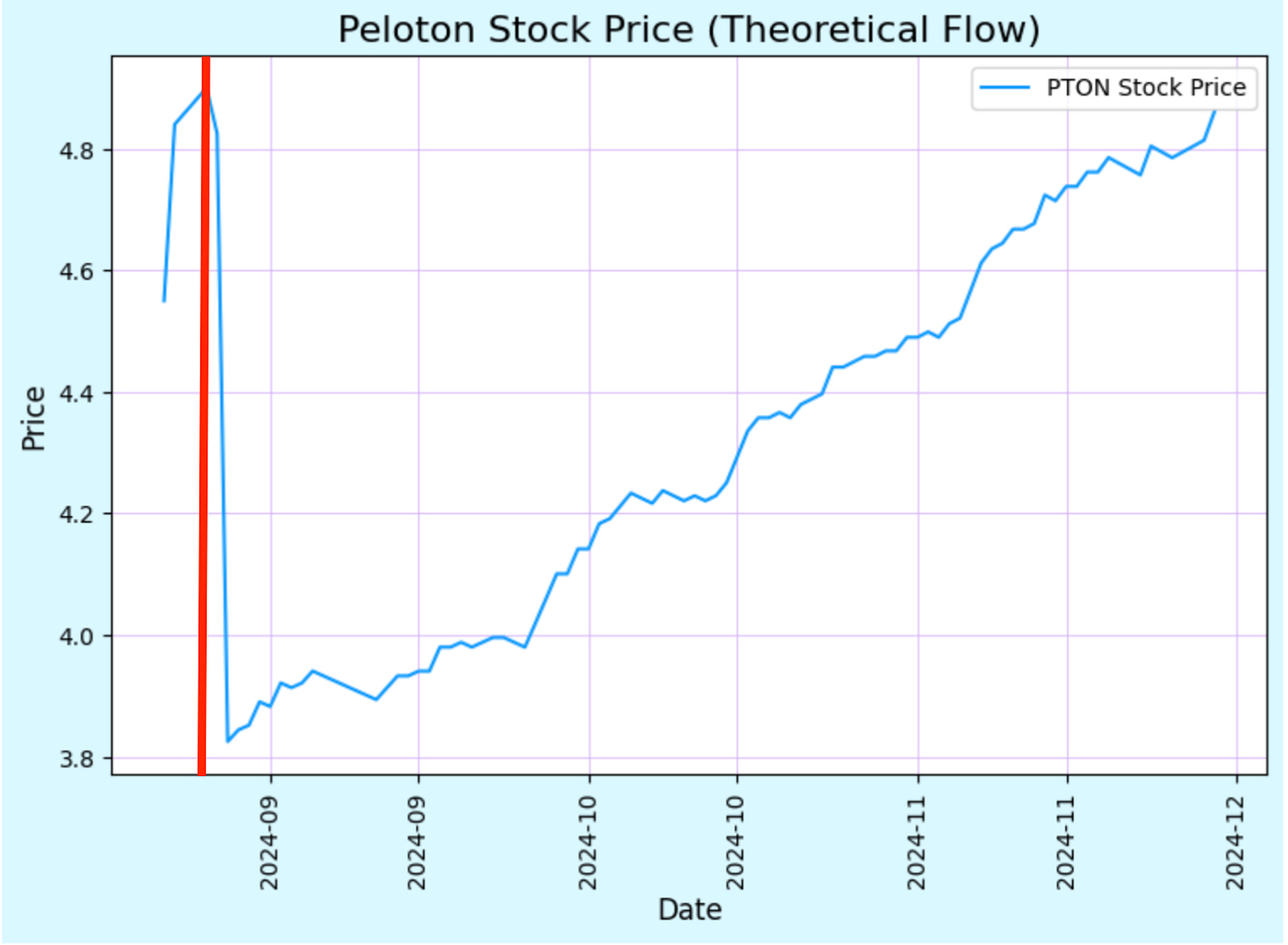

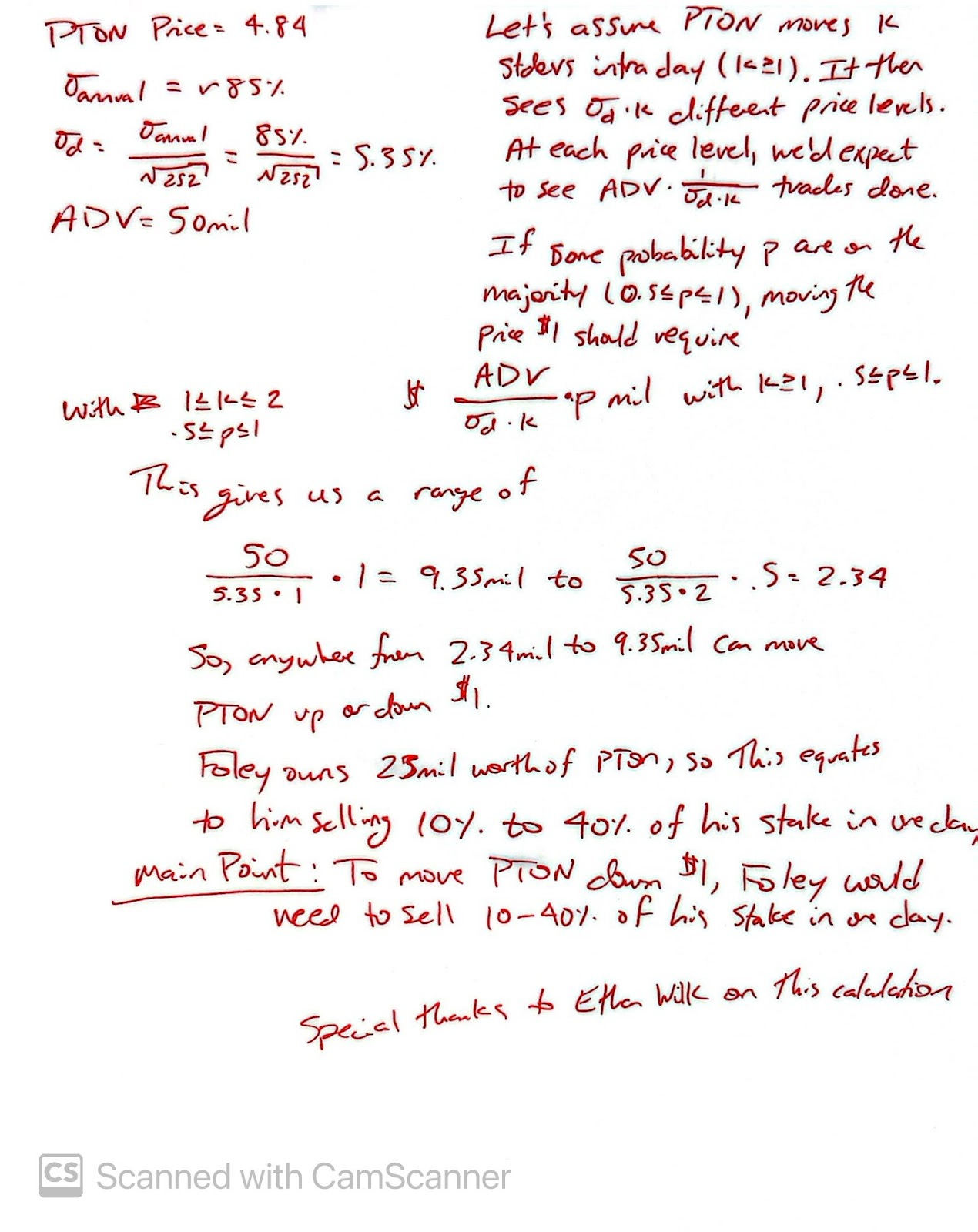

To make the example work well, let’s assume Foley is forced to sell out of 20% of the rest of his PTON stake today to pay for an upcoming mortgage payment on one of his mansions. What effect will that have on PTON’s price? This is a difficult question to answer, but I estimate it in the Appendix at ~$1 price impact.

So, we understand that $4.83 is the fair value for Peloton and we also understand that Foley’s selling should knock down PTON by $1. By betting against Foley’s flow, traders can profit off the temporary dislocation. Below, I’ve plotted a theoretical path of Peloton stock as it gets destabilized from the Foley flow before recovering back to its “fair-value.” This is obviously a simplified scenario and the path back to $4.83 isn’t likely to be this smooth, but the general principle should remain. This trade is in “utility-price space.” Foley’s utility function (prioritizing near-term lavishness over long term profits) led him to trade at poor levels (Figure 7).10

Figure 7: Hypothetical Illustration of Peloton Stock Price in Response to Foley Flow

Utility Arbitrage Alpha — Future

While flows can dislocate markets in both LLMs and SIMs, my view is that UAA is probably best suited for LLMs as it is much easier to trade against NEPs in larger markets. There are far more non-economic flows in larger markets and more liquidity in which to capitalize on these dislocations. This is a point that may be contentious and perhaps needs significantly more research to back up, but it isn’t a super important point. I believe UAA exists in all markets, large or small, and it is likely a sustainable alpha. There is a tremendous current towards a deeper understanding of markets and securities, making Informational Alpha increasingly difficult. However, transacting in price-utility space should continue to be profitable, as there will always be non-economic buyers and sellers (and players willing to try to capture this). Like IA, UAA will continue to be harder to find as hedge funds and shrewd traders gain a better understanding of flows and the utility functions of other players. But, I think because of the huge quantities of flows and NEPs in the market11, there are—and will continue to be—ample opportunities for UAA.

Conclusion

My current viewpoint is that Informational Alpha has become increasingly difficult in large, liquid markets. Structurally, I think it is difficult to have an IA moat in LLMs. I think the competition in IA in LLMs has significantly increased over the past 10-15 years for the following reasons:

The incentive structure of other LLM players to spread information after they’ve discovered it.

The proliferation of information on the most liquid markets, enables all players to have access to vast data.

The sheer competitiveness and amount of wisdom players have learned about the largest markets. In effect, the low-hanging fruit has been picked.

While the landscape for Informational Alpha in small, illiquid markets has certainly gotten more difficult, I think it is more sustainable in the medium term for the following reasons:

There are relatively few players in SIMs and the overall competitive environment is lower, enabling diligent traders to find inefficiencies.

Because of the illiquidity, the incentive structure is to keep IA private, not public.

While I see Informational Alpha as increasingly difficult, I think Utility Arbitrage Alpha is a byproduct of the service equilibrating traders offer. Because UAA offers a service and doesn’t require a “dumber” player in the market, it is likely less competitive. While I tend to think LLMs are a better place to find UAA, I think UAA exists in all markets but requires a deep understanding of the players and their utility functions. I think UAA will continue to be profitable as hedge funds and NEPs continue to have a symbiotic relationship. Furthermore, because of the relative size of NEPs relative to arbitrageurs (used very loosely), I think UAA serves as a decent breeding ground for future alpha.

Finally, it’s worth underlining a key point—many successful trades incorporate elements of both IA and UAA. Importantly, if you can understand your informational advantage and then a large flow knocks the security’s prices to greater inefficiency, you should capitalize strongly. Not all trades fall neatly into one bucket. But, investors should deeply understand where their alpha is coming from.

Thank You!

Thank you for reading until the end! I hope you enjoyed the piece and feel free to reach out if you have any questions.

Appendix

Figure 8: Assumptions Behind Peloton Slippage (Ethan Wilk Deserves a Shoutout Here)

I could write an entire Substack piece on my thoughts on risk/how to measure it (and perhaps I should), but this will have to wait.

The astute reader may have correctly surmised that I wrote this hungry, before dinner.

For simplicity’s sake, we are ignoring discounting here.

Let’s pretend there are a number of real money players also involved in the debt who are willing to lend their bonds to Banana.

While I didn’t mention the volatility of the trade, I assume that the vol was relatively low given the binary outcome of the trade. On a risk-adjusted basis, this seems to clearly be a good trade.

A former coworker and I estimate this at ~$2.6bil of capital to move NVDA $1. For those interested in the assumptions involved in calculating this, feel free to reach out.

Hindenburg Research is a prominent example of someone sizing up their position, then leaking it. HR knows they don’t have the capital to push prices to efficiency themselves, but by alerting others to their information, all players can become fully informed, pushing prices to efficiency.

This argument, in my view, is rather pedantic.

More likely, these funds have both fundamental models and flow models and always have a view on the fundamentals of a space as well as the ways flows have impacted prices.

This ignores the possibility for reflexivity, where flows can change prices which can then effect fundamentals. Perhaps Peloton could have raised additional debt when the stock was at $5, but now that it’s at $4, it can’t raise more debt and the fair value of the stock actually is $4! This is a complication for another time.

If we assume mutual funds, CBs, and corporates are non-economic players (arguable!), the quantity of capital deployed is more than enough to allow for significant UAA into the future.